the knowledge of most worth, whatever it may be, is not something one has: it is something one is… The end of criticism and teaching, in any case, is not an aesthetic but an ethical and participating end: for it, ultimately, works of literature are not things to be contemplated but powers to be absorbed.

Northrop Frye, The Stubborn Structure

As the Fall semester begins, with all its anticipation, energy, trepidation, and more… so many cultural and technological changes and experimentations upon humans and their learning, directing, and doings… I find more and more that we may be entering a kind of “dark ages” for reading and writing – a time when few, specialized alchemical, spiritual, learned enclaves (monasteries mostly) preserved the materiality of human learning and culture for hundreds and hundreds of years… that otherwise would have vanished to our access.

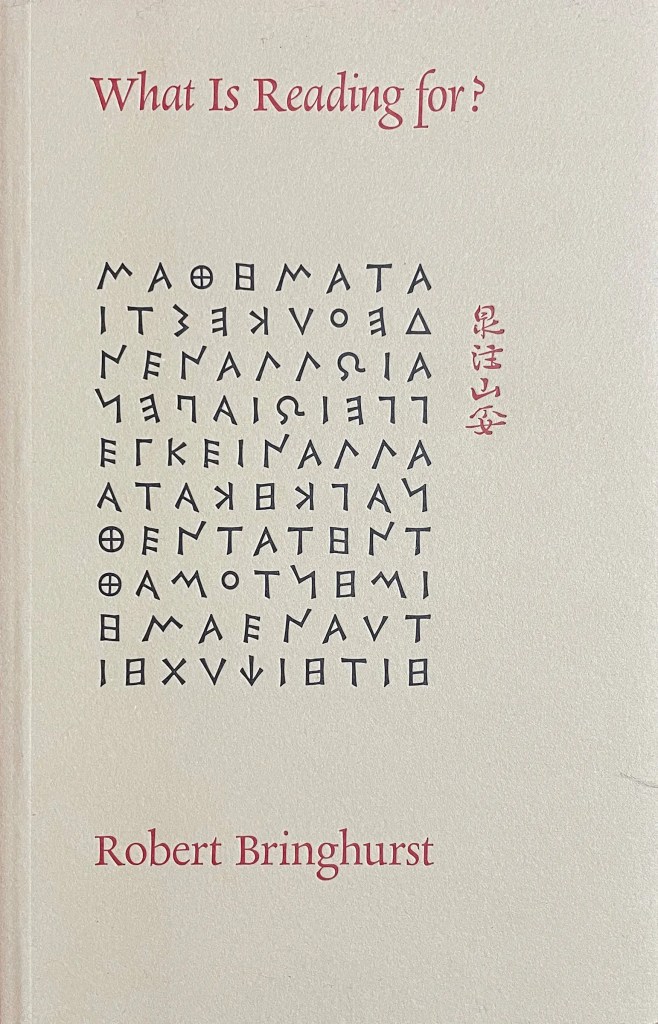

Following are some sections of Robert Bringhurst’s wonderful small beautiful printing of an incredible talk delivered orally – “What is Reading for?” – which I fervently recommend you borrow or find for the whole river of its beautiful pathway of winding deep riches and reflection. https://scottboms.com/library/what-is-reading-for

Now some samples from Bringhurst…

“In the narrow sense, as we all know, writing and reading refer to something done only by highly organized, agricultural, and management-oriented groups of human beings: making and deciphering visible signs for this normally invisible and almost intangible but nevertheless exceedingly dangerous stuff called human language. After that kind of reading and writing gets going, it’s borrowed by people who aren’t so management-oriented: oddballs like me, who want to use it to give stories and poems and ideas and musical compositions an independent, semipermanent material existence: to let them speak for themselves, like paintings and statues.

“That kind of reading and writing is usually called artificial. It only exists where highly organized groups of humans go to a lot of expense and trouble to sustain it. But some of the things that are done with it, and some of the things it is used for, are not artificial at all. Margaret Atwood, you might remember, spoke about that crucial shift, from the writing of quartermasters and clerks, wanting to keep control of what they possess, to the writing of thinkers and listeners, wanting to keep in touch with what they’ve heard. Both kinds of writing are, of course, still with us, but it is the latter kind of writing that we associate with writers, and so with readers too…

“…If it sounds like writing loves rivers [he’s just spoken of the earliest traces we have of places we have evidence of inventions of writing, all which occurred along rivers], that’s because writing loves agriculture, and that’s because writing is, itself, an advanced form of linguistic agriculture. “Writing is planting,” it says in a poem I remember from somewhere – and reading is harvesting. Harvest time, you’ll remember used to be a time of celebration, but harvesting was work. There are actually places where humans still do it themselves, and where they remember that it leads, in turn, to more work – threshing and milling, peeling an cooking, pitting and drying – and then to still more celebration. In industrial societies, all of these crucial activities are now mechanized. I have a strong hunch that the urge to digitize books and distribute them over the internet to reading machines grows out of a similar dream: a desire to build machines that will write and edit and print and read the books for us, so we can go upstairs and watch our screens…

[here he spends a few sections tracing the evolution of the materiality of oral language to script and then to printing – to scribal cultures to typography – to preservation and dissemination methods and technologies, concluding with]: “You see what I’m getting at. Reading could have a rich and interesting future, because it does have a rich and interesting past. But if no one remembers that past, it may not mean much to the future…What I think is that a great work of literature deserves fine typography and printing, just as a great theatrical script or a great piece of music deserves a great performance. The idea, of course, is that these things can add up – and ought to add up, at least once in awhile, as a form of celebration. If reading good books is physically pleasant, people just might spend more time reading those kinds of books, and might want their friends and neighbors and children to do the same. And reading good books just might make some of them into wiser, healthier people. That, as I recall, is how education is supposed to work. It’s not necessarily supposed to raise the GNP or make everybody rich, but to make every life more likely to be a life worth living, whatever life it is…with a reasonable degree of intellectual and spiritual independence…”

[more soon to follow…]

So beautiful and so meaningful, Thank you dear N Filbert,

Love, nia

Linguistic agriculture -Writing is planting – reading is harvesting – Jesus that’s good (said not in vain but fully)

The book is so rich…pt 2 of a tiny section tomorrow 🙂 & thanks (for Bringhurst)

Pingback: Reasons I Library, or the Book and Living (pt. 2) – All my Words are Silent