This continues readings from Robert Bringhurst’s beautiful WHAT IS READING FOR? begun in previous post.

Bringhurst runnels his way through various carriers and purposes of diverse sorts of publications and materials across history – from the more disposable to the mostly artifactual and permanent – reasons why they are preserved, and types of reading they promote and engender… from here he enters the new and ephemeral format called the “electronic book” that our culture currently and earnestly proffers us…

“The digital book is a rotation, not a revolution. It is another turn of a wheel that is turning all the time. It’s a newfangled toy and may be some fun, but it is also just the latest stage in the continuing degradation of the outward from of the book. The most perishable, and most visually disappointing, form of text yet invented is text on a screen. It’s the perfect medium for a society that believes, in its heart of hearts, in the basic futility and irrelevance of what it finds to say [italics mine]. And plenty of what we say does fit that paradigm. But because the electronic book exists, it will also get used, like the early scripts of the Neolithic accountants, for statements of lasting value. Real reading and writing take place on the margins of empires. That’s just how it is. You read the books, if you want to read them, however you can [italics added]. And we do.

“…real writing involves a lot of revision. Real reading involves a lot of re-reading, in just the same way. The text also needs to be free of distractions…discontinuous reading has a long history…That’s how we’ve always read dictionaries, atlases, recipe books, and other works of reference. It’s how we read discontinuous matter, of which there is plenty. Reading with a capital R is something else: an attempt to live up to the world in which we live, and to those ever-renewing models of the world known as books – with, if you like, a capital B [italics mine]. That kind of reading involves taking the plunge. It involves immersion – not for an hour…but for days, for weeks, and in some sense for life.

[Bringhurst now discusses beneficial aspects of coded, electronically transmittable formats of writing/s, particularly for learning and scholarship]

“Running searches for this project made me conscious of two things. First, what it was doing was not reading; it was simply light housekeeping, aimed at making my own and other people’s future reading easier, more thorough, and more comfortable. Second, what enabled me to do what I was doing was the labor of other literary housekeepers extending over more than twenty centuries, fundamentally unfazed by a good many changes in tools, techniques, and materials [the librarians, title so or not, italics mine]…from scripts to manuscript to print to electronic database, papyrus to paper to screen, the sweeping and dusting and laundering have continued as they must.

“All this housekeeping aims at a single thing: allowing reading to continue. Why? For the same reason we walk, talk, and make love. Because that’s how the species transmits itself from yesterday to tomorrow.

“It will, I guess, be clear that one of the things I think reading is not for is taking complete managerial control of the verbal environment, or of any body of text within it. Where literature is involved, that is not even what writing is for. Outside the dreary realm of purely utilitarian language, reading and writing are both ways of getting involved in, not taking control of, the great ecological fact of the matter, otherwise known as What there is to pay attention to, mirrored for us in What there is to say.

“Clearly, people take pleasure in having control, or the illusion of control. But the freedom to skip around whole continents of text like a Martian in a flying saucer, scooping up sentences here and there, is pretty much wasted on genuine readers, because those are the people who know that reading is mostly for making discoveries, learning how and what things are – and who know that to do much of that, a flying saucer is not what you need. You have to walk through the text, and for that you need good eyes, good feet, and lots of time.

“So what’s in the future? To be honest, probably starting all over from scratch, with a small and impoverished population in a badly wounded environment, recreating oral culture bit by bit, and possibly working back up to some kind of writing. But in the meantime? In the short term, it’s quite easy to say what we need for digital books to succeed for real reading.

[Here he provides 5 propositions with descriptions: 1. Free from the grid… 2. a non-radiant display… 3. high resolution… 4. good letterforms… 5. as few bells and whistles as possible]

“In other words, it would be a fine idea if the digital book functioned a lot like earlier books. But how it works matters less than how we treat it. If, to us, it is nothing but a commodity, that will mean we have forgotten how to read, and no book then will help us.”

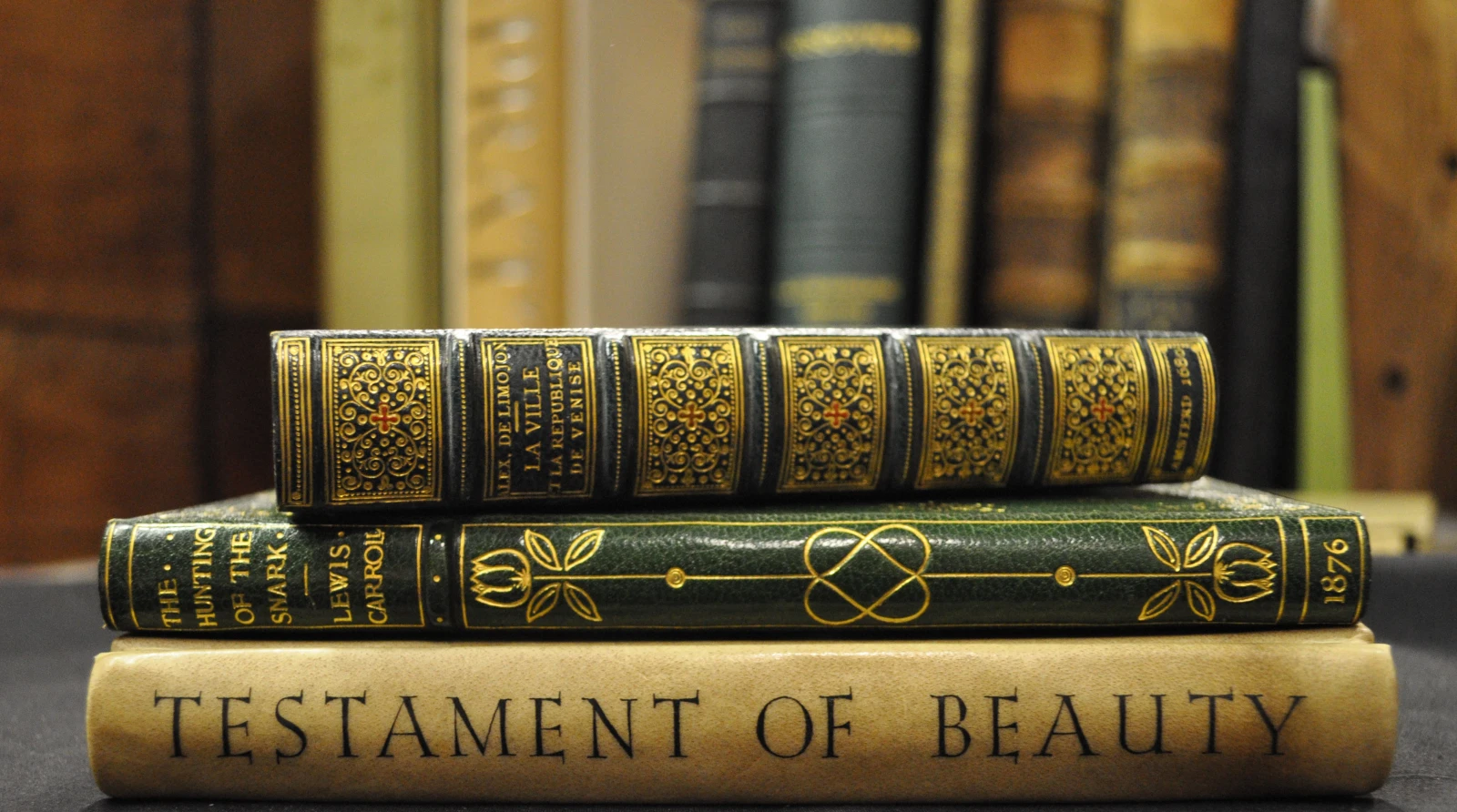

I am hoping it is evident to see why the practice of preserving actual oral, written, and material forms of culture and our stories and languages we wish to preserve – the work of transcribers, translators, interpreters, writers, printers, craftspersons and artisans – actual things we can pass along at will, preserve ourselves (not dependent on corporate servers, access rights, power companies, or any technologies we ourselves cannot build/rebuild) i.e. – the traditional public library, religious libraries, archives, special collections, museums, and living human transmission and communication – matters so much to me. If you are librarians, or keepers of books, and realize the costs of not controlling access and availability of what they offer to any in our communities who wish to participate in via reading – please fight for the preservation of semipermanent materials.

For more on the ecology of language and material transmission (and to hear the wonder of Robert Bringhurst’s knowledge and communication and thinking) please see also: What is language for?

Thank you for your time and carrying the flames of these passions (if you share them). Much of my grief and ache comes from witnessing the “weeding,” “de-accessioning,” “optimizing,” (all synonyms for destroying in my case) many unreplaceable government documents, “compactly shelved” historical publications, and other very beautiful and impressively produced human artifacts that I still believe would have been welcome and desired by humans to preserve throughout the world.

See also: The Most Amazing Books People Found in a Dumpster …

I have always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of library

– Jorge Luis Borges